Against Fractional Complimentarity

Why men and women don't divvy up the virtues

Two fun bits of book news. The Dignity of Dependence was reviewed by Matalyn Vennerstrom in Law and Liberty and she writes:

Autonomy-based feminist theories don’t just misunderstand women; they reflect deep misunderstandings of the human being, per se. Perhaps the strangest and best thing about this particular feminist manifesto is that it isn’t really about women (or inadvertently about men). It’s about human beings. As the author puts it: “the fundamental question is whether our view of persons is large enough.”

And second, I’m delighted to announce that The Dignity of Dependence was Christianity Today’s pick for best book of the year in Politics and Public Life. The best price right now for The Dignity of Dependence is directly from Notre Dame Press, because it’s 40% off with “14HOLIDAY.”

Sr. Carino Hodder has an excellent piece about same-sex societies and the masculine vs feminine virtues in The Lamp. (She’s also the author of The Dignity of Women in the Modern World). As a consecrated religious, she’s interested in the ways that two same-sex communities of friars and sister live out the same rule in their gendered communities:

The differences between male and female religious communities are particularly intriguing—and, I think, particularly edifying—when we compare communities within the same spiritual family, such as my own Dominican family. These are communities bound to the same Rule of life, exercising the same institutional charism, formed in the same history and spirituality and ordering their common life by the same structure of internal governance—and yet, nevertheless, not reduced to a bland interchangeability by this shared structure.

When a Rule and a charism are embodied in a living community, the divinely given contours of that feminine or masculine embodiment become clear, made manifest exactly where they are meant to be: in human relationships marked by charity and mutual help. A Dominican friar is not a sister without a veil; a Dominican sister is not a friar who chants in a higher pitch. The commitment to living by a Rule calls us to find dignity, not danger, within our sexual differences, and to acknowledge sexual diversity without giving in to the temptation to invent a corresponding sexual hierarchy.

Sr. Carino Hodder and I are in agreement that there are some broad tendencies you can observe across same-sex groups. She notes that convents often have little notes and labels on everything, while the friars have barer walls. I’m happy to concede if my husband tells me there was rough-housing during one of his high school’s single sex refectum periods, I can guess pretty accurately which one.

But this doesn’t lead Sr. Hodder to see men and women (whether in vows or not) as dividing up human virtues and habits. She writes:

All of this might suggest that my experience of religious life will have made me sympathetic to our current discourse on femininity and masculinity. It absolutely hasn’t. For me, our current obsession with arriving at an ever-more-structured definition of the differences between men and women, our drive to define even more tightly masculine and feminine virtues, vices, roles, and responsibilities, simply doesn’t map on to the reality of life in a single-sex system like a convent. What is a woman’s job? What is a man’s job? I have no idea, because in the convent there are simply jobs, and unless I or one of the women I live with find it within themselves to (for instance) take out the trash, put up a shelf, have a necessary confrontation or make a tough decision regardless of the emotional tension it might cause, then these things are simply not going to get done. We have neither the time nor the inclination to wonder if this might actually be a job for a man when it is, quite simply, a job for this present moment in this particular religious house. It becomes a feminine act by virtue of being carried out by a human being embodied female. It is, if you like, a human act played in a feminine key.

Here, she’s drawing directly on the work of Sr. Prudence Allen, who describes and rejects what she calls “fractional complementarity” in her magisterial The Concept of Woman.

Abigail Favale, author of The Genesis of Gender, has an excellent gloss on Sr. Prudence Allen’s work (for those not able to commit to her 500p tome) at Church Life Journal. Favale writes:

There are three basic theories at play: unity, polarity, and complementarity. What differentiates these theories is how they hold to or depart from the twofold principle of equality and difference. Unity theories, which we can trace as far back as Plato, emphasize equality while downplaying difference. Polarity theories, which can be seen in many ancient traditions, including Aristotelian philosophy, emphasize difference at the expense of equality, thus affirming a hierarchy of superiority and inferiority between the sexes. Complementarity theories attempt to hold both equality and difference in a fruitful tension…

Fractional complementarity, then, sees the sexes as complementing one another because they each reflect partial or fractional aspects of a whole human being. Fractional complementarity tends to divvy up various human traits and virtues into pink and blue lists: men are more rational, let’s say, and women are more emotional, so together they make up for one another’s deficiencies—together, we account for a well-rounded human being.

Integral complementarity, in contrast, views men and women as whole human persons in their own right. The full range of human traits and virtues is open to cultivation by both sexes. Our complementarity, then, is synergistic—it does not complete a lack but enhances a whole, resulting in a fruitful collaboration that is more than the sum of its parts.

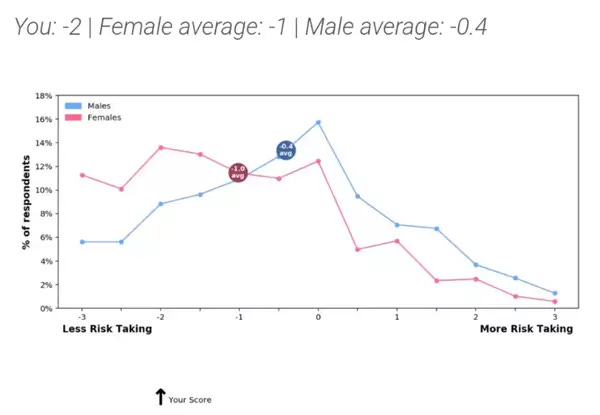

Favale notes there are some stark, first order differences between the sexes (fertility being the most obvious) but that the empirical data shows that second order differences of personality traits don’t divide men and women neatly. Overlapping bell curves… overlap, even as there is a general drift or tendency. I’ll highlight one of several graphs she explores in detail:

Men and women do differ in their average scores on risk taking, and the differences are more pronounced at the extremes. When you look at the tails of the bell curve, you’ll see bigger gender skews, but in the most common ranges, men and women are strongly mixed. As Favale sums it up:

To put it another way—this means that sex stereotypes are often based on atypical males and females, those who exhibit a more pronounced extreme of a sex-associated personality trait. The female who is closer to the male average (and vice versa) is often presented as the outlier, the exception, when in fact she is closer to the norm.

And now here comes the strongly Catholic part. Favale blends Sr. Prudence Allen and St. John Paul II to discuss what our embodiment means for the virtues:

A man exhibiting compassion is not reducible to a woman exhibiting compassion—not because the trait per se is different, but because that trait is being embodied by a male, and thus takes on a paternal, rather than maternal, character.

Picture, in your mind, an icon of Joseph holding the Christ child. Now picture an icon of Mary holding the Christ child. If we were to describe these two images in terms of abstract traits, we would likely have a lot of overlap—tenderness, love, protection—and yet these images are not interchangeable. They are meaningfully different, irreducible to one another. The difference arises from embodiment. In his Letter to Women, John Paul II refers to this as “iconic complementarity”—our bodies carry an “iconic” meaning, a “powerfully evocative symbolism” that reflects some of the most sacred metaphors in divine revelation. A man can reflect, in a distant but important way, the iconic character of God as Father and Christ as Bridegroom, just as a woman reflects the iconic character of the Theotokos, the God-Bearer, and the Church as Bride.

I find this pretty compelling… but then, before I was a Christian, I was an atheist with strong Platonist leanings. The idea of imperfectly participating in a Form is part of my ethical vernacular. But I don’t assume this image rings true to all Other Feminist readers, not even the Christian ones.

So here’s what I’m wondering:

I love this because it puts into words an intuition I’ve had for a while about, as was said, dividing the virtues into pink versus blue.

I’m interested in why fractional complementarianism is so attractive to many? It certainly seems to be on the rise in some segments of Christendom - perhaps as a reaction against the extreme flattening of sexual differences in the broader culture?

Whatever its cause, it also seems just as disembodying as what it’s reacting against (and the two feed each other, if that makes sense.)

This is occasioned by me being deep in studying for a final for ecclesiology, but integral complementarity vs fractional complementarity seems to better communicate the distinction of clergy and laity within the Church.

It’s not like priests and laity are each part of a whole Christian. Rather each has a full call to holiness but they complement one another.

Does this make sense to anyone else? Does anyone know of someone who has already discussed this?