Can There Be an Abortion Compromise?

Examining the roots of our divide at Fairer Disputations and NR

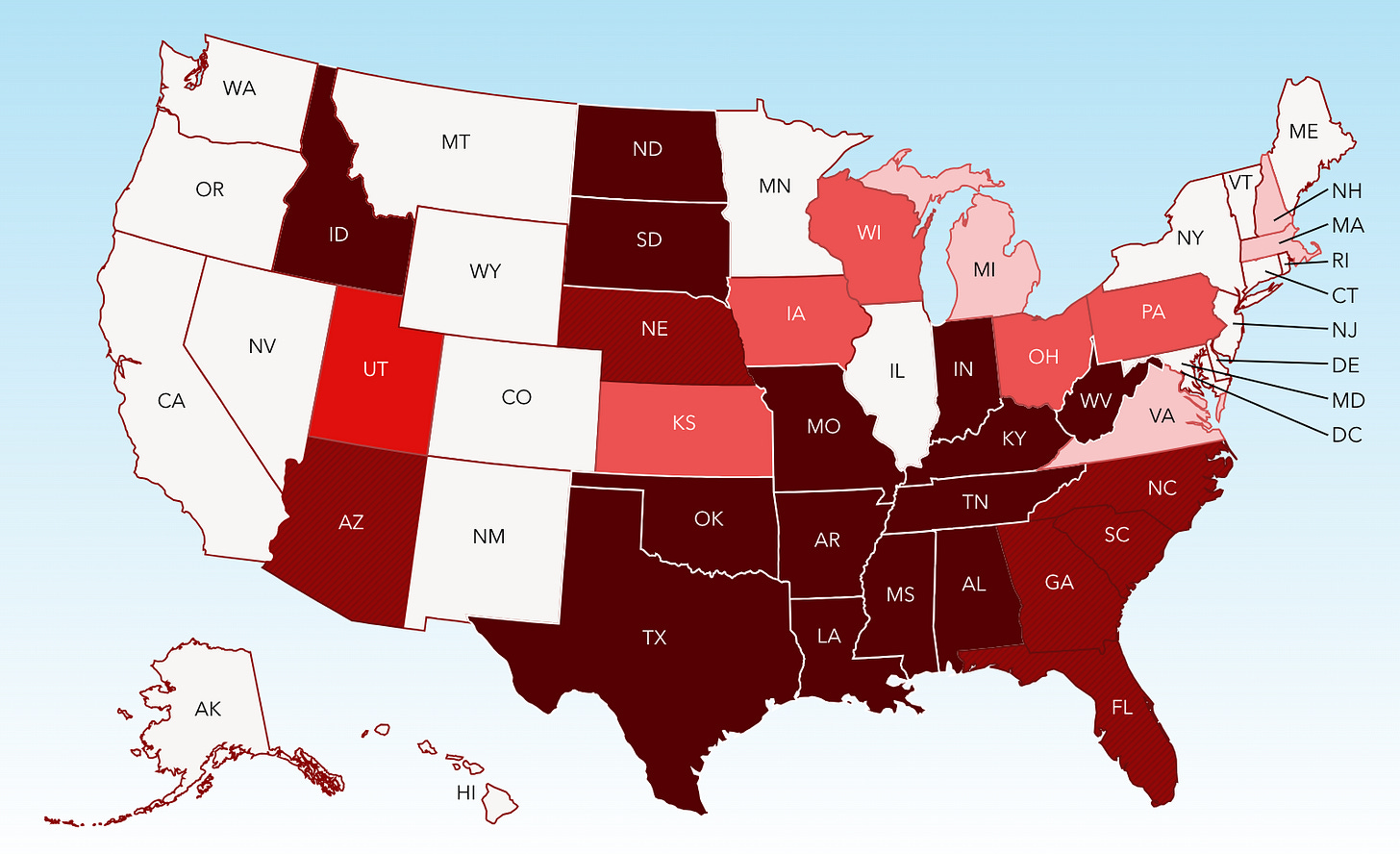

What does a post-Dobbs America look like? So far, it’s a sharply divided nation with piebald policy on abortion—essentially illegal in some red states, unrestricted in many blue ones.

Viewed one way, it looks like a stable arrangement—after all, in many red states abortion was technically legal but practically very difficult to obtain pre-Dobbs. Each state passes the laws it likes, and abortion funds attempt to cover the costs of travelling to a more abortion-friendly state.

But just because neither side can take territory easily doesn’t mean this stalemate is stable. I can’t help but think of Abraham Lincoln’s remarks at the 1858 Illinois Republican State Convention.

"A house divided against itself cannot stand."

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.

I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall - but I do expect it will cease to be divided.

It will become all one thing, or all the other.

At National Review, I wrote on why there will be no abortion detente. It was prompted by Trump saying he didn’t like heartbeat bills and expected the two sides could meet in the middle. But abortion isn’t an issue like marginal tax rates, where you can average the asks from both sides.

Nearly all abortions (93 percent in the 40 states reporting their data) occur in the first trimester (13 weeks). A pro-life “compromise” that sets bans after the first trimester would leave nearly all children in the womb at risk. And contra Haley and Trump, it’s not likely to leave pro-choice activists feeling appeased either. Some activists have reacted with frustration to Democrats’ emphasis on sympathetic plaintiffs and life-threatening pregnancies. Activists don’t want storytelling about “good abortions” to imply a parallel set of “bad abortions.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has refused to back laws that clarify “life of the mother” exemptions and create safe harbors for physicians. ACOG policy is to “strongly oppose any effort that impedes access to abortion care and interferes in the relationship between a person and their healthcare professional.”

An abortion compromise isn’t likely, as Trump imagined, to leave us “with peace on that issue for the first time in 52 years.” Pro-lifers can win only by making their case on the merits, directly to their neighbors, not just to judges. It doesn’t make sense to claim you’re fighting only for “federalism” or that you care a lot about the exact threshold for state referenda and direct democracy. The instinct to fight by feints and misdirection — for example, through TRAP laws (targeted regulation of abortion providers, like mandating wider hallways) — lost its relevance when Roe fell.

In the meantime, Louise Perry has been weighing what compromises on abortion she can stand to make. Perry, the author of The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, is still pro-choice, but in her First Things essay “We Are Repaganizing” she explores her uneasiness. She write:

Here’s the problem for the feminists busy sawing at the branch on which they sit: The same Christian ideas that grant feminism its moral force carry other implications. Though women are a vulnerable group by virtue of their being smaller and weaker than men, there is another group of human beings who are weaker still. A group with no ability to defend themselves against violence, or to proclaim their rights. The very smallest and weakest among us, in fact. Whether we like it or not, we cannot place the protection of the vulnerable at the heart of our ethical system without reaching the conclusion that the unborn child ought not to be killed.

This presents a problem for feminism, because a prohibition on abortion places on women burdens that it does not place on men.

I joined Holly Lawford-Smith, Robert P. George and Helen Dale for a symposium of responses, from both sides of the abortion divide. I was struck by the opening of Perry’s essay, and focused on the question of how systemic violence is made invisible.

Louise Perry’s “We Are Repaganizing” opens with a conversation with an archeologist. Roman brothels are recognizable by the clusters of baby skeletons—the children born of commercialized couplings, killed after birth, and tossed in the trash. Perry notes that our own time hides its killings better. At modern abortion clinics, “the remains are usually burned, along with other ‘clinical waste.’ There will be no infant skeletons for archaeologists of the future to find.”

In pagan cultures, the annihilation of the vulnerable was virtuous. In ours, it is cloaked in euphemism (“terminating a pregnancy” not “killing a baby”; “death with dignity” not “prescribing poison to the elderly”). Our delicacy is a small, fragile pledge of our resistance to paganism’s bloody frankness. Our killings are quiet, civilized, and we work hard to find ways to describe them as an act of generosity to the victim, not a rejection or a willingness to spend their lives to buttress our own.

What intrigued me most in the pro-choice essays was that both Helen and Holly see part of Perry’s error as being too vulnerable to the claims the weak make on the strong.

Helen: I’m not persuaded that morality giving priority to the weak and vulnerable is always wise […] a key Roman insight—suffering doesn’t improve people—is left to shock moderns, who don’t test whether it is true.

Holly: It’s worth noting that the valorisation of the weak is not quite the same thing as egalitarianism. We might retrospectively oppose the social hierarchies that resulted from the Roman admiration of the strong (powerful, wealthy), and yet think that merely reversing that social hierarchy to venerate the weak has its problems too.

That left me with some questions, which I’ll turn over to you:

From the perspective of a woman who had an out of wedlock pregnancy and faced an almost overwhelming assumption from my friends and social circle that I would abort (not, thankfully, from my now-husband, my family, or my closest friends), I don’t know what it will take to turn the cultural tide on abortion. I was not your “typical” unwed mother - I was older, very professionally established, and in a great financial position. From my perspective (raised in the “safe, legal, and rare” era by parents who considered abortion acceptable only in dire circumstances), it was never on the table - indeed, I quickly realized that having my son was a God-given opportunity to reorder my life around something other than myself and my selfish desires. But it became apparent almost immediately, once I was in that position, that essentially the entire edifice of female professional-managerial class life was built on abortion. At least for women of my social class, the post-sexual revolution world is one in which success is possible only if you make yourself a worker first - a creature that can be dedicated, above all else, to first the pursuit of educational achievement and then the pursuit of career achievement, with all other demands (children, husband, family, friends, community) deprioritized.

Louise Perry has noted that this world makes many (if not most) women unhappy, and I do think that’s true - virtually every mother I know that works full-time wishes that she didn’t, because she wants to prioritize caretaking (of her children, aging parents, and the family as a whole). There are broad social classes where unwed mothers typically do not choose abortion, but so long as the class that sits at the top of the economic hierarchy, that controls policy and sets the terms of employment for most of the country, and that exerts overwhelming cultural power is built upon abortion, I do not think we will see a broader shift toward a culture of life. It angers me, honestly, that we act as if my ability to be a fully realized human being requires legalized killing, but that is the approach we’ve taken rather than remaking our professional-class world to reflect inherent difference between men and women.

As a pro-life woman, I don’t want to go *back* to a pre-Roe, pre-sexual revolution world. I want to go forward to a different world that accommodates a broader vision of success, fulfillment, and happiness - one that reflects what most women want, rather than trying to force women to want, and strive for, lives that look just like men’s.

I don't really much the difference between our culture and the Romans other than the fact that we pretend to care about the weak. We valorize the strong and the wealthy, and we marginalize the weak. The heresy that God rewards the virtuous with material blessings is pernicious in our culture---and let's all be honest--the idea that people who have cancer or heart disease or other chronic diseases somehow made lifestyle choices that "caused" the disease is common too.

Unless we change our ways and put some real financial and logistical support behind family formation, I would expect that it's going to be really tough to convince women to have babies. I look at what my kids are going through--do you know how much it costs just for deductibles and out of pocket co pays for prenatal care and for a hospital delivery? No young family should start out thousands of dollars in the hole just to PAY for childbirth! That is barbaric!

I don't think anybody "wants" an abortion or views it as a good thing. Women just can't see how they can raise a child. There are animals that kill their young if they feel under threat--rabbits are the best known example, but I've seen birds do it too. If you want to prevent abortions then make prenatal and maternity care free. Mandate paid parental leave for at least 6 months. Provide a cash stipend for each child under 12 or so--the age at which kids are old enough to spend an afternoon without adult supervision. Create economic conditions that will allow one full time wage earner to support a family.

If the government won't do those things, the government has no business forcing women to bear children.