Doubling Down on South Korea's Gender War

"Women can hurt men, too"

In the first week of the Flowers of Fire bookclub, the book focused on legal fights against harassment and assault. In the second section, “Where Did All the Girls Go?” the author focused a little more on online communities and cultural shifts… not all of them for the better.

Patrick T Brown and I continue our conversation at Fairer Disputations this week:

Here’s an excerpt:

Patrick: In a sense, the Internet acts like a technological shift that increases the returns to scale for something like upskirt photos. Instead of a guy privately ogling someone on the subway, he can now take a photo, upload it, and participate in a perverse sense of community. It goes from gross on an individual scale to mass-produced, self-replicating objectification.

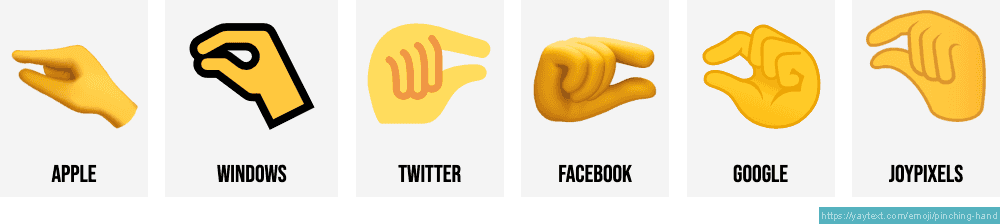

So then it’s not surprising when some of the women try to mirror back the online abuse they received somewhat fascinating, particularly that some men were apparently thin-skinned enough to really be bugged by the 🤏 meme for it to cause actual anger and unrest…

It also reminded me of a bit in last year’s “Saturday Night,” which features the female SNL cast members rehearsing a sketch in which they are dressed construction workers, cat-calling a scantily-clad Dan Akroyd. The joke lies in the fact that, of course, it doesn’t work to role-reverse sexual comments, because women don’t have that implicit physical power over men.

Leah: I understand why there’s a kind of power in simply showing men how little they like being treated the way they treated women, but a real weakness of the mirroring that the women of Megalia engaged in is that they’re rooting their community/sense of solidarity in carrying out acts they know to be evil.

And yes, I think they justify it a little in thinking it doesn’t have the same sense of threat behind it when a woman does it—a woman who catcalls or mocks a man might make him uncomfortable, but he’s not worried she’ll follow him into an alley and overpower him. But one of Jung’s notable quotes (from a sociologist) is:

“Beyond such a radical message that ‘women are also humans,’ [these women] left the earth-shattering message that ‘women can hurt men, too.”

It’s a pretty hollow victory! It reminded me of nothing so much as Shylock’s big monologue in The Merchant of Venice which begins with the appeal to common humanity in “Hath not a Jew eyes?” but ends with mutuality in the form of mutual threat, “If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?”

There’s a lot of good that comes out of the online communities women built. It’s hard to imagine winning real policing reforms to so-called “minor” crimes like taking upskirting photos (how M. Pelicot initially attracted police scrutiny) without building a mass movement.

I’ve been part of group chats that convene in order to address an urgent problem, but, as they continue on, slide into riffs and running jokes on serious matters. There’s a “can you top this?” dynamic to a text channel—it’s got the same kind of cheerful suspense as my kids trying to keep a balloon from touching the ground.

And when there’s a light, transgressive frisson, it makes you feel like even more of a community—you wouldn’t make these jokes without real intimacy.

I delete a lot of half-written jokes, both in groupchats and on twitter.

I don’t have a fully formal rubric, but I’d say these are some of the considerations.

Is this appropriate matter for kidding?

Let’s take as a given that I’m funny (or believe I am). I’m going to be able to come up with jokes that go beyond what it’s prudent to josh about—I can’t just filter based on whether it’s witty.

For a practical example: there were false reports that Francis Fukuyama had died a month or two ago, and I thought a lot of the initial jokes about his end versus “the end of history” were pretty funny! I had a few come to mind, too.

But, if he was dead, then the first thing I needed to do was pray for the repose of his soul, not riff on his scholarly work.

When I found out it was a false rumor, I joined in on the fun.

Does adding my voice make this a pile-on?

Part of the problem of the internet is that it makes what might be a reasonable response from one person into an onslaught when it scales. I sometimes think the best way to respond is to roll a 20-sided (or 100- or 1000-sided) die depending on how many other people have already weighed in, and only add your voice when you roll a 1.

Even when I don’t pull out a randomizer, thinking about scale helps me pause and think about whether my additional riff on the topic is helpful or harmful.

Does this distance me from prayer?

If you’re not a praying person, you could frame this in different ways: “Does this coarsen my conscience?” “Does this lead me into habits of contempt?” But for me, it’s the formulation above that gives me the clearest, pricking-est answer.

When I make a joke that’s rooted in active contempt or in treating someone as setup to a punchline, not a human soul, it’s bad for me. You can debate what dose is broadly tolerable, but I can’t really handle the stuff well.

The big thing for me is that I’ve seen friends (across the political compass) become worse people through this dynamic of friendships/community rooted in slightly mean or transgressive jokes. I absolutely believe you can come together around a righteous cause and wind up severely disfiguring your conscience along the way.

I was pretty troubled by this section because of how communities formed around hitting back, and the kind of hitting back that’s about contempt. There’s an ensuing backlash, but it’s the internal reaction, not the external one that worries me most.

A theme in each chapter and story Jung presents is a sense of the shared pain and resentment that women in South Korea felt over their awful mistreatment by men in their society, especially online. This communal pain and anger creates the kind of solidarity necessary for effective social change, but it can easily perpetuate the desire for revenge. Those emotions need some sort of outlet individually and collective. Can this be done in a healthy way at such a large scale, when the group that is mistreated is so large (ie all women)? I think addressing a group’s shared sense pain and anger is one of the difficulties of contemporary gender discourse. How can men and women acknowledge the fraught dimensions of their present and historical relations to the other without falling into the snares of revenge and contempt?

I asked a writer friend of mine to do a piece on the underused, old English word, "scoff". I think it is the perfect word for today's political climate, one group scoffing at the other, without real arguments being considered. Propaganda often takes the form of "mockumentaries", clips of silly interview questions and answers, strung together without context, designed to be scoffed at, to enkindle anger after the bitter laughter. I would suppose the obscure word used in the New Testament, Matthew 5, "raca" is pretty close to "scoff"?