[Earthsea] Strength's Appeal to Despair

When we judge the power of a tool by its danger

This is week seven of our summer Wizard of Earthsea book club. This week’s chapter is “The Hawk’s Flight.”

It’s always funny to reread a book you read as a teen. It’s the pivotal moments that stay with me, so I’m often surprised by the pacing of the book when I return. Which is to say, a fair number of Ged’s chapters end with him losing consciousness!

Each time he succumbs, to the Shadow, to overexerting his power, to cold, to hawk-shape, he seems to have come through a new birth by touching death. LeGuin often explicitly names him as a new creation, with his old self foreign to him now.

I like the way that genre fiction heightens ordinary human experience. I think many of us go through these moments of discontinuity in smaller ways. And I’m very interested in Ogion’s tutoring as a path toward integration.

But before I turn to the end of this chapter, I want to talk about the power Ged is tempted by in the Terrenon Stone. When Serret brings him to see it, the Stone (and the spirit bound within) is safeguarded behind locks like a treasure. The work of approaching it lends it a kind of pomp and majesty. But Ged speaks passionately against the awe Serret displays:

He spoke with a grave boldness: "My lady, that spirit is sealed in a stone, and the stone is locked by binding-spell and blinding-spell and charm of lock and ward and triple fortress-walls in a barren land, not because it is precious, but because it can work great evil. I do not know what they told you of it when you came here. But you who are young and gentle-hearted should never touch the thing, or even look on it. It will not work you well."

Gd encounters a problem that we confront, too. How do you warn someone against a malign power without lending it an air of romance and challenge? Isn’t anything worth guarding worth glimpsing?

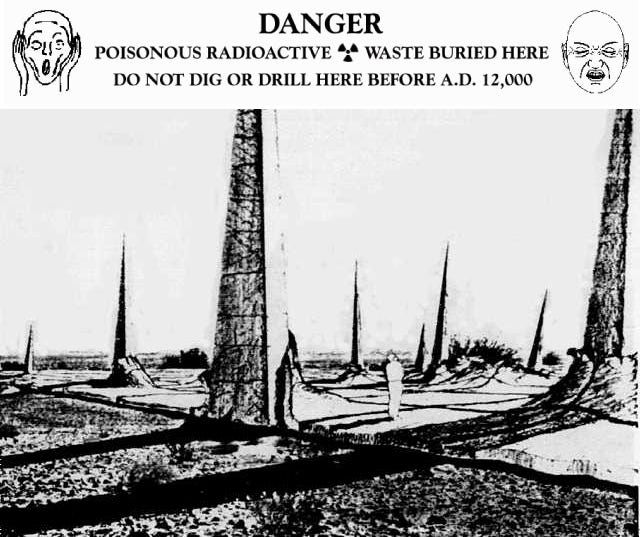

It reminded me strongly of one of the proposed warnings to place on long term nuclear storage, which might, due to its large, layered defences, attract curiosity and excavation. (I wrote a short RPG about the passage of time and the attraction of mystery and danger inspired by these warnings). I’ve excerpted the nuclear warning below, the full text is here.

This place is not a place of honor.

No highly esteemed deed is commemorated here. Nothing valued is here.

What is here was dangerous and repulsive to us. This message is a warning about danger.

The danger is still present, in your time, as it was in ours.

The danger is to the body, and it can kill.

I don’t think this message would have dissuaded Serret or her Lord. The greater the warning, the greater the danger, the greater the power to be wielded, if you can master it.

Ged is tempted by that power, since he is already oppressed by one malign-seeming power. If he is already in despair, with no clear way to defend himself, how much harm is there in trying something, anything.

What recollects him to himself is Serret’s urging that only darkness can drive out darkness. He knows that is not true. Only light can rebuke darkness—if he cannot find light, he will still gain nothing from cleaving to deeper darkness.

Outside of the context of our bookclub, I was frustrated by the Ohio Issue 1 ploy to change referendum laws before an anticipated amendment drive to guarantee abortion access.

There’s plenty of room to disagree about the right threshold for lawmaking and Constitutional amendments through direct democracy (personally, I do think it should take more than a bare majority).

But the restrictions went further, with a number of burdensome requirements (requiring a quorum of signatures from every county in the state, which seemed much more transparently about quashing referenda.

I’ve gotten into some arguments with friends, who say you can’t be precious about proceduralism when lives are on the line. But this feels more like the call of the Terrenon to me. It seems like this short-term, pro-life tactic comes from a place of despair, assuming our neighbors are unpersuadable.

Near the end of this week’s chapter, Ogion, who has kept his silence, used his husbanded words to tell Ged this:

A man would know the end he goes to, but he cannot know it if he does not turn, and return to his beginning, and hold that beginning in his being. If he would not be a stick whirled and whelmed in the stream, he must be the stream itself, all of it, from its spring to its sinking in the sea. You returned to Gont, you returned to me, Ged. Now turn clear round, and seek the very source, and that which lies before the source. There lies your hope of strength.

It’s hard to live rightly when we ignore the very beginning and source of human life. But it’s also hard to communicate that truth when we take our present division from neighbor for the whole of our story.

Last week, I asked you about your own experiences of trying to flee from, but without somewhere to run toward, in the same way Ged has been doing. I appreciated all your comments, and Ogion weighed in, too, in this chapter:

If you keep running, wherever you run you will meet danger and evil, for it drives you, it chooses the way you go. You must choose. You must seek what seeks you. You must hunt the hunter.

And Martha shared a story from our own not-as-obviously-enchanted world:

Before I got pregnant with my kiddo I had been trying intermittently to cut down on my drinking. I stocked the fridge with seltzer, drank less when I went out with friends, etc. But I was running *away* from drinking. It felt like a loss to be filled. When I got pregnant with my son - and esp. after he was born - not drinking no longer felt like a loss. I knew that continuing to drink would, for me, mean that I would enjoy our time together less. Running toward him has resulted in me having no interest in drinking since.

This week, I’d love to hear your thoughts on the chapter especially:

The theme that struck me most about this long, engaging chapter was slavery.

"There was no such comradeship among this crew as he had found aboard Shadow when he first went to Roke. The crewmen of Andradean and Gontish ships are partners in the trade, working together for a common profit, whereas traders of Osskil use slaves and bondsmen or hire men to row... Since half this crew were bondsmen, forced to work, the ship’s officers were slavemasters, and harsh ones. They never laid their whips on the back of an oarsman who worked for pay or passage; but there will not be much friendliness in a crew of whom some are whipped and others are not" (ch. 6).

"'The Terrenon...will tell you that name.' 'And the price?' 'There is no price. I tell you it will obey you, serve you as your slave.'"

The second quote, about there being no price since using the Terrenon is as easy as slavery, was jarring for me, as it probably was for Ged as well.

Slavery obviously exacts a price from the enslaved person. It also comes at the price of the morals of the slaver and slaveholder. A more subtle price of moral injury, a disorientation or callousness, may be paid by anyone who witnesses or is complicit in and feels powerless against the injustices of slavery.

And lastly, as we see among the oarsmen, society pays a price for slavery, in the form of division.

I wonder to what degree slavery is responsible for the "dour" Osskilian culture. The Terrenon wants Ged, and later on his gebbeth, to "become a slave of the Stone." It has already enslaved Lord Benderesk and Serret. The man in grey also had "a queer beaten look about him, the look almost of a sick man, or a prisoner, or a slave" (ch. 6).

It's sometimes said: "Poverty is the natural state of the world. The real question is: Why is anyone rich?" I do not actually believe slavery is the natural state of the world. I think violating others' human rights so flagrantly is too unpleasant (for the human slaveholders) for slavery to become widespread, in the absence of strong systemic incentives that warp society into blessing it.

Still, I think it's worth asking, given that slavery happens in Osskil (and, it's been mentioned, in Kargad, the South Reach, and Pendor), why does it not happen in many other places in Earthsea such as the Andrades and Gont? We can't entirely blame the Terrenon, which does not suffer human pangs of empathy, because regions other than Osskil engage in slavery. Though perhaps the Terrenon has a very long arm of influence, or something similar to it is influencing each of the other slaving territories.

Why not slavery? Are the strong systemic incentives that have warped some Earthsea societies into blessing it absent from other societies, and why? Or is it sometimes that the non-slaving societies have a stronger cultural defense against it? Why are "pirates, slavetakers, [and] war-makers hated by all that dwelt in the southwest parts of Earthsea" (ch. 5), rather than joined?

I don't expect to find answers to these questions in this book, but it's worth asking them about the real world too. How can we shore up our cultural defenses against systemic incentives toward bad things?

I wish I had a real-life story about disarmament, but the best example I can think of comes from a sci-fi story (http://www.intergalacticmedicineshow.com/cgi-bin/mag.cgi?do=issue&vol=i31&article=_003). In it, a clan of aliens finds a colony of humans on their planet, and the colony is built right over top of the aliens’ unhatched and vulnerable children. So a stand-off ensues in which the leaders of both sides really want to find a peaceful resolution, but the competing interests and difficulty of establishing good faith between utterly different species makes it complicated. There’s actually a couple scenes where one character stands unarmed before another, using their vulnerability to ask the other to stand down. And it more or less works — not without injuries, but they do avoid an all-out war. It’s a compelling story.

More directly related to Earthsea, it’s encouraging that Ged isn’t tempted by the power of the Stone, even at a time when he thinks he’s lost all his own power. Earlier in life, he wasn’t properly afraid of either raw power or evil magic. He’s paid a high price to learn the lesson about not messing around with evil magic, but it does seem like he’s learned it.