Festivals of Particularity

Investing the ordinary with gravity by linking it to persons

It’s a sick day for one of our girls, so I wanted to share two recent essays I really enjoyed on loving things in their particularity, not according to their merits on some absolute scale.

In C.S. Lewis’s The Four Loves, he talks through the four classical types of love: storge, philia, eros, and caritas, and storge was the one I’d never really seen discussed (let alone praised) before. You could translate it as fondness, and it’s easy for that to sound trivial or sentimental.

One way I think about storge if that it’s the kind of love you have for that one particular tree that sits three blocks from your house and marks the turn onto your street. It’s not that that tree is the tallest or most beautiful—it might not even be your favorite kind of tree in general—but it is your tree in a way no other tree is.

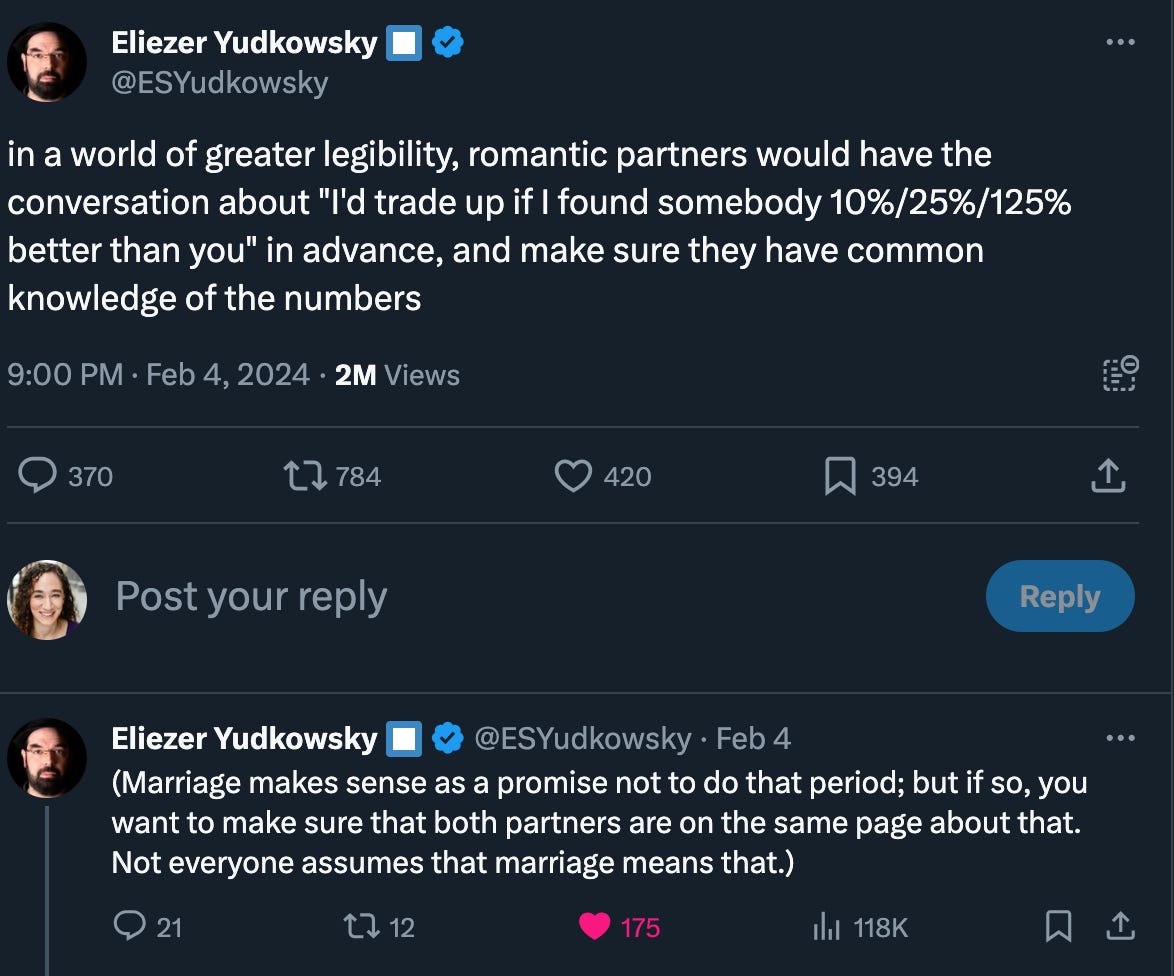

And cultivating fondness and valuing it as a real kind of love is a good inoculation against, well, this:

If every loving relationship is a meritocratic relationship, it is necessarily fragile. A foundation of slow-growing storge is part of how we become stickers, without forfeiting our judgement.

In an essay for First Things, James Matthew Wilson describes a holiday his family invented for themselves:

My children, the last four of whom were born in Pennsylvania, could pass through a gate in our back fence and walk to the library or the playground without crossing a street. The anniversary of the day we moved into our house—August 30—we pronounced “Stickers’ Day,” and celebrated it with dinner in the back yard, followed by the telling of stories or a game of catch or freeze tag. In this, we quietly honored the work of William Stafford and Wendell Berry, who admonish Americans to be “stickers,” to settle in a place and stick, rather than “boomers,” always on the move and chasing the next boom.

Notably, Pennsylvania is not where he wants to be a sticker (the essay is titled “Sweet Land of Michigan” and he ultimately finds his way back to his longed for home). But while Pennsylvania is his, he regards himself as Pennsylvania’s and forms his family’s life accordingly.

After reading the essay, my husband and I marked our calendar for our first celebration of Stickers’ Day (also in August), and we’ll have to come up with what it looks like this summer. (I’d be amused by cooking at least one sticky food).

Stickers’ storge love can come out in the smallest things. In Nuclear Meltdown (a substack I’ve been enjoying), Jim Dalrymple II tells the story of his grandma’s unexpected memorial:

Each year at Thanksgiving, my family eats a special roll that is spiraled and buttery. In the family cookbook, they’re called “refrigerator rolls” because the recipe calls for making the dough one day then storing it in the fridge overnight before baking.

But in recent years, I’ve noticed that some of us have started using a different name: “Grandma Maxwell Rolls,” after the grandma who originated the recipe.

I’m not sure why this change happened, but the unexpected result is that Grandma Maxwell is now among the most-mentioned deceased members of my family. Just this holiday season, I probably told my kids five different times about going to Grandma’s house and having the same roles that we still make today. I don’t think anyone intended for this to happen, but with a name like “Grandma Maxwell Rolls,” stories naturally come up.

I love this story, and it’s a good reminder we may be remembered longest not for our best or worst qualities but simply for our repeated actions, which become part of the texture of someone else’s life.

We like to name dishes in our house (a garlic and walnut pasta we made up on Ascension Day is now always Ascension Pasta, no matter when we eat it; this Smitten Kitchen dish is “St. Joseph’s One-Pan Miracle” for similar reasons). It gives the dish echoes, leading us to think about our past and future of eating together.

One thing that comes to mind is the renaming of objects that tends to happen with families: for example, in my family we call clementines and mandarins "tasties" because one day my little brother was struggling to peel one and yelled out "Open up, TASTY!"

Another example of something that has become imbued with meaning for me is something I refer to as "the family pile." My family lives overseas so we tend to see each other for a 3-4 week trip once per year. Throughout the year, there is a shelf in my apartment dedicated to next year's trip. Some of the things it holds are socks left behind from a previous visit, a box from a chocolate shop that gives you a discount for returning them, and souvenirs from various trips. When I left my parents' house this year to visit my maternal grandparents, I also took my mom's pile to my grandparents, and came back to my parents with stacks of magazines, cookies, and more that they had saved for my mom. The family pile is a reminder of a lot of things: that there will always be a next visit, and that we still rely on each other for material help even when living far apart.

Naming one’s car is not unusual. Naming it for its affable ugliness might be.

The most reliable car I’ve owned was named Lonesome George, after the Pinta Island tortoise of the Galapagos. Lonesome was an old Toyota a mechanic we knew had refurbished, so that it ran well, but its defective dark-green paint, which had worn to a dull, pitted desert patina after just a few years in a non-desert climate, had not been refurbished, making Lonesome resemble a tortoise — and making him really inexpensive for his reliability. Sadly, our Lonesome eventually gave up the ghost, about a decade after the real Lonesome George did. But our Lonesome had a good run, and I don’t know if I can get as attached to a nicer-looking car.

I’ve also run across more than one person with EDS (Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome) who humorously names problem body parts. Arguably, no treatment for EDS works as well as relentless bodily discipline — but no treatment for EDS, including relentless bodily discipline, works all that well. We all know (or should know) that we can’t control other people, and that even people who really annoy us are still people, with human dignity and so on. But remembering that our own bodies have dignity, as well as limits we can’t reasonably be expected to control, in the midst of bodily dysfunction can be harder.

“I call this knee Karen because she’s always complaining, and that one Jennifer because she’s such a spoiled princess,” doesn’t sound very affectionate — or fair to the Karens and Jennifers of the world — but it’s more affectionate than what we might be thinking about our lemon knees without the nicknames. A name, even one of contemptuous stereotype, confers some independence to a thing, acknowledging it’s not just some cypher for our domination — no matter how much others, however well-meaning, expect us to dominate our bodily problems as if they were cyphers.