Maintenance as Tenderness

How we learn to love small acts of stewardship

This week, I’m sharing highlights from your comments on “The Romance of Regularity.” I appreciated reading your thoughts on how we remember the gravity of small acts of diligence. Next week, I’ll share some of your comments from this week’s discussion of “Gift-Work Becomes Women’s Work.”

Discussion of gift-work versus market-work became a big part of the conversation during Capita’s panel on “Building a Culture of Solidarity that Works for Mothers and Children.” You can watch the discussion here.

Sophia suggested a playful way of taking everyday work seriously.

My friends and I call it "Studio Ghibli-ing our lives." A pile of greasy dishes is slightly less dreadful when you can imagine it lovingly animated with each item plunging into a wobbling cloud of soapsuds. If you can imagine it this way, you find the steps to bring it to a shining sparkly-clean reality become a little easier.

Studio Ghibli has come up repeatedly, both here and in our previous discussion of stories without conventional climaxes.

I tend to have a less adorable tone in my own visualizations, picturing doing dishes in more of a decontamination mode. Slow, serious, and sterile—but in a heroic way. But what I think Sophia and I have in common is a teleological sense. In some way, we’re taking care of the dishes which want to be clean and need our help. That sense of making things whole is very motivating to me.

LK pointed us toward a sermon by St. John Henry Newman. In “The World’s Benefactors,” Newman meditates on St. Andrew, the first called of the apostles, of whom, nevertheless, “little [is] known in history, while the place of dignity and the name of highest renown have been allotted to his brother Simon.”

Our lesson, then, is this; that those men are not necessarily the most useful men in their generation, not the most favoured by God, who make the most noise in the world, and who seem to be principals in the great changes and events recorded in history; on the contrary, that even when we are able to point to a certain number of men as the real instruments of any great blessings vouchsafed to mankind, our relative estimate of them, one with another, is often very erroneous: so that, on the whole, if we would trace truly the hand of God in human affairs, and pursue His bounty as displayed in the world to its original sources, we must unlearn our admiration of the powerful and distinguished, our reliance on the opinion of society, our respect for the decisions of the learned or the multitude, and turn our eyes to private life, watching in all we read or witness for the true signs of God's presence, the graces of personal holiness manifested in His elect; which, weak as they may seem to mankind, are mighty through God, and have an influence upon the course of His Providence, and bring about great events in the world at large, when the wisdom and strength of the natural man are of no avail.

Melanie shared a poem that I’m reluctant to excerpt—you can read the whole thing here. And Leslie suggested Tish Harrison Warren’s Liturgy of the Ordinary. (I second the recommendation).

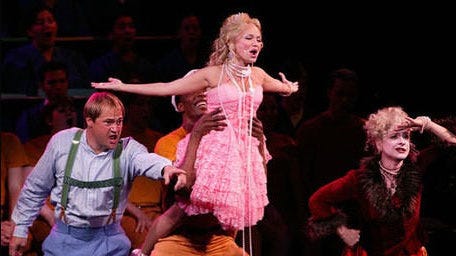

Shaina suggested the closing song from Candide, in which the humbled protagonists say at last, “We're neither pure, nor wise, nor good. We'll do the best we know. We'll build our house and chop our wood. And make our garden grow.”

I love this song and (presumably to Voltaire’s chagrin) I’ve prayed with it in hard times. One thing I particularly like about the recording, rather than my solo singing, is the way the song become so strong at the end. This is one of those moments where I wish I studied music theory, so I understood how it gets so much bigger even as the orchestra drops out. What had been simple becomes a solid wall of sound.

But that’s what I think we’re all discussing when it comes to the romance of regularity. What seems simple becomes, by patient repetition, thick and strong and piercing.

I was thinking about this piece today when watching (and listening) to Bluey, the Australian children's cartoon. They use music and tone to make the most mundane childhood activities and games heroic and/or deeply meaningful and impactful (which they are! the act of forming a child's identity makes the smallest actions transformative).

I barely know Candide, but looking at the sheet music (shh! https://aimsgraz.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/M-Make-Our-Garden-Grow-Candide.pdf) what first jumps out at me is that the early verses don't give much of an impression of harmonic or rhythmic direction. Meters are often changing, and the melody and harmony present very few surprises. We're wandering unhurriedly across the territory that the song's beginning suggests — neither roaming far afield nor facing down an unbending railroad track. The accompaniment is gently underscoring the vocal line, without making unwelcome interpolations.

The first sign of real momentum and excitement comes from a rising stepwise pattern (think of the vibraphone line that Jonathan Tunick's arrangement includes in the last verse of Losing My Mind), which crops up in short fragments as early as measure 14 (a middle voice accompanying the man's "We're neither pure..."), but which is fully articulated at length when the ensemble enters ("Let dreamers dream..."). This is also when the low register of the accompaniment introduces strong, insistent offbeats (which the orchestration gives to the timpani).

The gradual expansion of voices and growing momentum in the accompaniment bring us to the full, harmonized, polyphonic, and unaccompanied choral passage. Where the accompaniment had been gradually expanding interest from static block chords to tolling timpani and our rising scale figure, by the time it takes over the choir adds complexity and density through the use of contrapuntal voices and countermelodies (e.g., the male voices' "our house, our house and chop, and chop our wood" in measures 58-59). So what you're perceiving as "a solid wall of sound" is the cumulative effect of (1) careful contrast with the preceding musical landscape, (2) gradually rising intensity, and (3) an impression of monumentality from strategic adornment of the musical surface (see also the architectural concept of "breaking up the mass," contrasting the façades of the East Building of the National Gallery and the equally majestic Natural History Museum a few blocks away).