Making Work Valuable Means Making it Visible

Your stories about refusing to hide household labor

Two weeks ago, our topic was the extra work you’re expected to do to make it looks like your work cost you nothing. The discussion was sparked by Meg Conley’s essay on hidden fridges and other elements of kitchen design intended to hide the work being done.

I appreciated the stories you shared about the pressure you felt to hide effort. Because of the volume of comments, I’m going to focus the highlights I pick on the alternatives or responses to this pressure that some of you have found.

I particularly appreciated your reflections on this question I posed:

What does a work space look like when the work is valued?

One commenter, who is also named Leah, said:

I aspire for all the rooms in my house to look like workshops — with everything stored visible-but-organized on shelves. This is the long-term vision, but it feels similar to the Montessori-style model you’re aiming for.

Watching Adam Savage’s workshop organization videos on youtube during the first year of the pandemic was very soothing to me; he was so happy to be solving real problems in his studio, and watching things get cleaned up and put away was the narrative I wanted to watch. This discussion reminds me of it because if you walk around his studio, even when everything has been put away, it definitely not minimalist — rather a dense, flexible arrangement of specialized tools and supplies. A single, fairly small space that can be flexibly transformed based on what project is in progress.

I really like this phrase “he was so happy to be solving real problems in his studio.” I like watching maker videos, too (and, um, sometimes videos of people getting rust off of a cleaver—it’s very satisfying!).

It’s a pleasure to see a problem sized up and solved well. There’s a delight in mastery that can be easier to bring to other people’s work than your own.

Meg Conley herself popped in to talk about plans for her own kitchen:

I keep going back to my kids' Montessori classrooms too. Like how can the kitchen be workspace that is also lovely to my eye, restful for my soul, inviting to the curious, or invigorating for the not-yet curious. It sounds like a tall order, but those classrooms really do it. And I am trying to be open to what that might look like, how that might feel. But I can't quite grasp the vision yet.

Tessa talked about how seeing work in other people’s homes made her feel more welcome.

I've been reading Charlotte Mason on atmosphere lately: what she says about cultivating a life-giving atmosphere for our children seems to go for our guests as well. […] I suppose I try to go for an orderly homeyness: orderly so that things can be done—meals, conversations, chores done together, clean-up accompanied by music or continued chat—rather than sterility or the appearance of sterility.

I find it helpful to recall what feels welcoming to me when I'm a guest: I appreciate feeling the character of a particular home (as well as signs of life—herbs drying, bread rising, laundry waiting to be folded), and I appreciate feeling that things have their place, so that I can more easily join in the work of the house while I'm there. When I'm visiting my in-laws, some of the best conversations happen as we're making food or cleaning up together.

I love her point about whatever is out revealing character. I’m more likely to go to to bookshelves in a new home than the kitchen counter to get to know my host, but both are an introduction to what the home is rooted in.

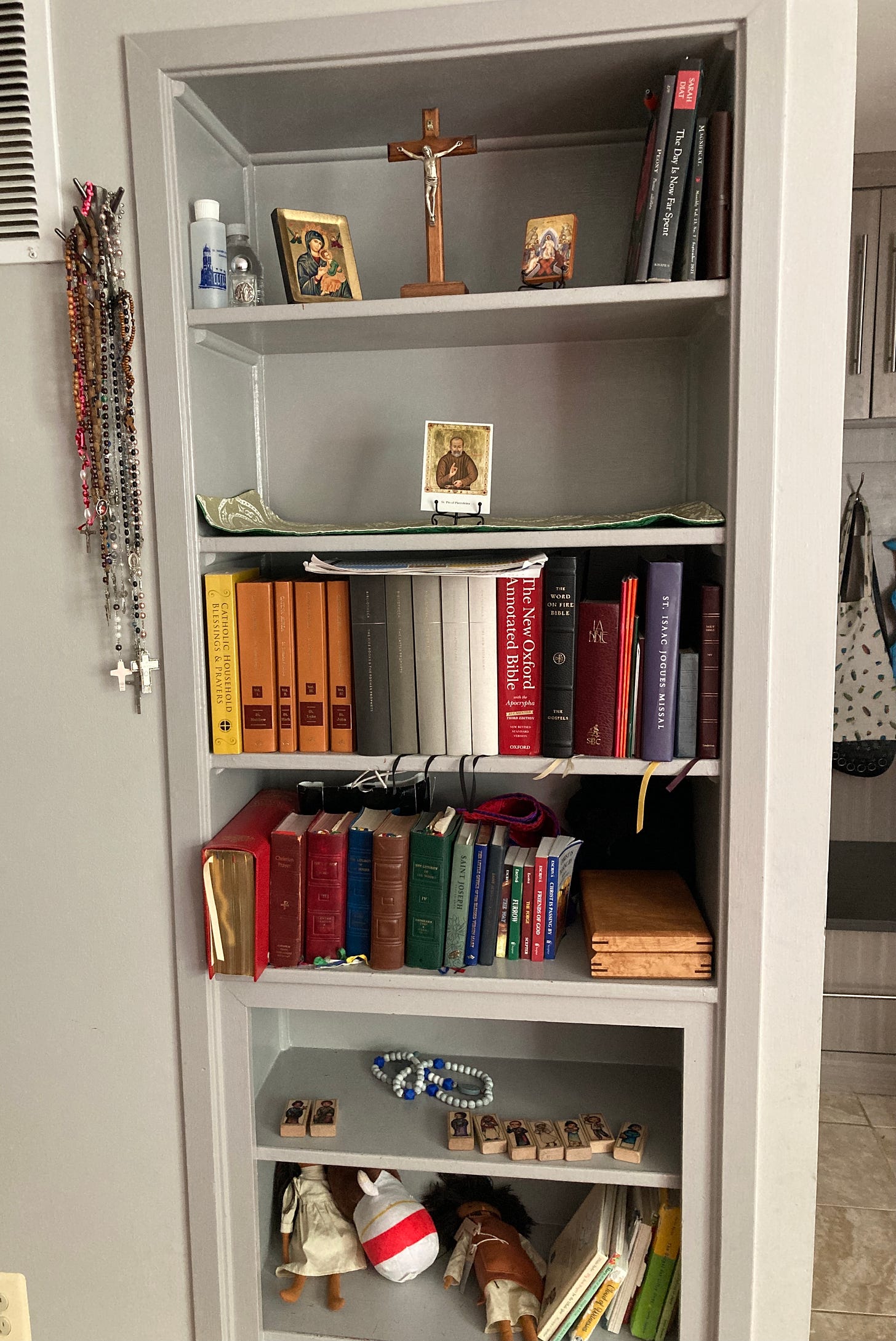

We set up our little oratory (inspired by the book of the same name) in the living room so it’s at the heart of our house, but I didn’t think of it as an example of visible work until I read Tessa’s comment.

I love having the rosaries right to hand. The goal is to treat them like the kitchen scale—too essential to daily rhythms of life to put away in a drawer. They need to be ready to pick up.

Finally, I loved these plans from Elizabeth:

I don’t necessarily feel much pressure to make domestic work invisible, per se, but I’m realizing that all the same, my home space isn’t designed to elevate this work. Some concrete things I’ve added to my dream home wish list as a result: a butcher block, rather than getting out and putting away cutting boards that are too small anyway; and a sewing table or better yet a sewing room, rather than letting my craft projects take over other surfaces and then berating myself for the “clutter”.

I’ve also been mulling over what it could look like to invite guests into household work. This feels like a norm that needs to be built together—that is, it’s a cultural change that one household can’t make alone. Rosaria Butterfield’s book The Gospel Comes With a House Key comes to mind because she writes about messy/unstaged hospitality. Often I feel like inviting guests over is mutually exclusive with doing chores...but what if instead I invited friends over with the stated purpose of doing chores together?! And then next time we go over to their house and do their chores together. Things could be so much better than current-state lonely drudgery if we could shift to seeing household work not as a perpetual barrier keeping us from getting to the fun stuff in life, but rather as a daily opportunity to build the world we want to live in.

When I give talks about my book Building the Benedict Option (a primer on building Christian community), I ask people:

What do you do alone that you wish you could do together?

And a lot of people say chores. Grocery shopping, laundry, cleaning, etc.—some people in the audience want that to not be private time, but to be a kind of work that’s enlivened by conversation. I think a little of the sewing circles from Louisa May Alcott’s books, but folks have mentioned doing this more in college.

When your lives are knitted into each other’s, you simply are together as chores come up. Getting together isn’t an occasion that has to be special and polished.