Two Years of Other Feminisms!

Writing on dependence, depending on readers like you

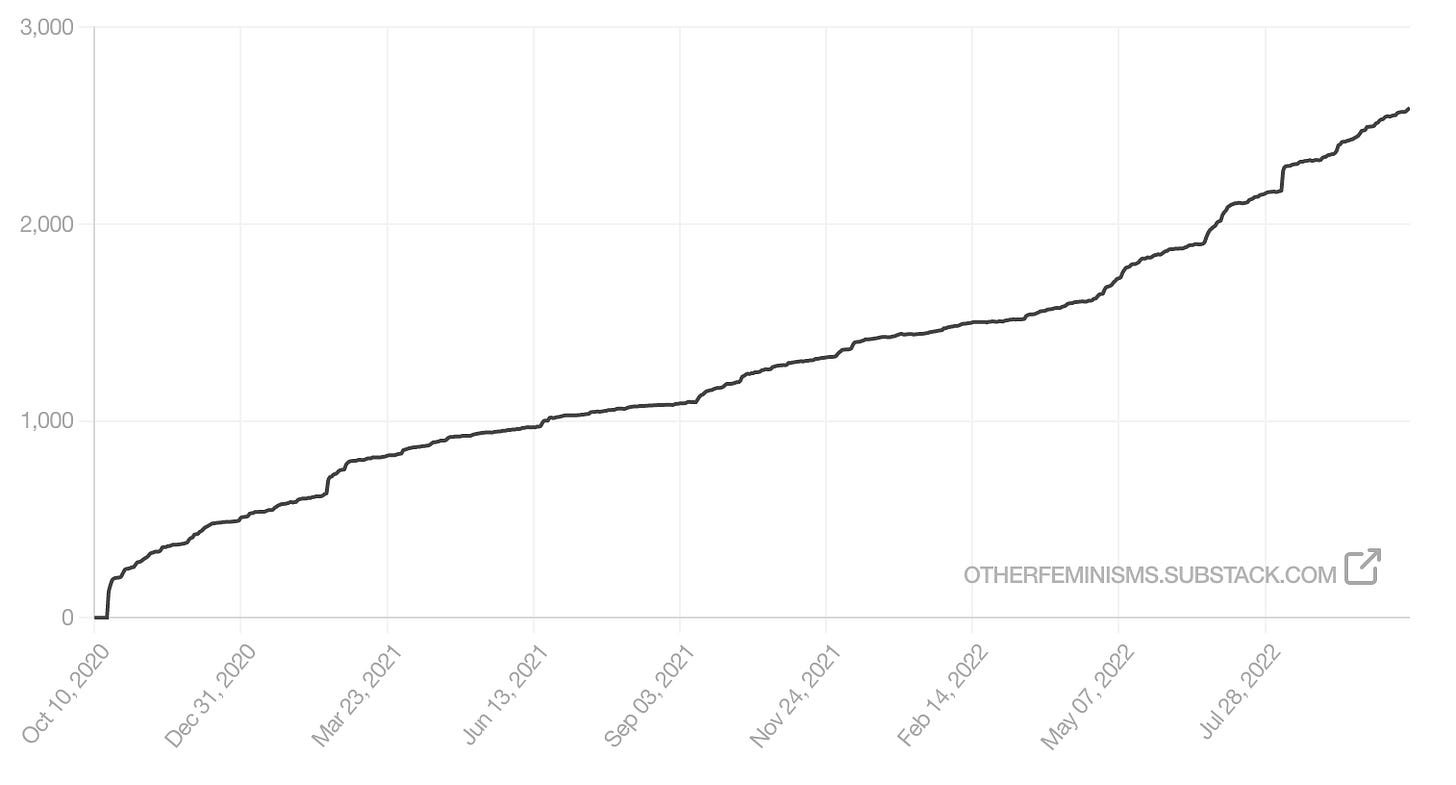

Other Feminisms launched two years ago today, with a starting readership of 132 people who signed up via a Google Form. At the time of drafting, you make up a community 2590 strong!

From the beginning of the project, I wanted Other Feminisms to be a substack, because I thought it was my best shot to have a sustained conversation with thoughtful readers. I like seeing familiar names in the comment threads, and seeing long-time readers speak for the first time. I appreciate how readers who strongly disagree with each other (or with me!) ask good-faith questions and read the responses carefully.

And I’m grateful to those of you who can afford to support Other Feminisms through a subscription and have made it possible for this to be an unpaywalled project. With two children under three, saying “Yes” to working on Other Feminisms means saying “No” to some paid freelance projects. Paid subscribers make it easier for me to pick the “Yes” to this project, by softening the cost of the “No” to other paid work.

To mark our community’s second anniversary, I’d like to share one essay, one quote, and two questions.

The essay

My essay, “Dependence,” for Plough is the closest I have so far to a manifesto for Other Feminisms. Here’s the key idea, a little compressed as I excerpted:

The liberal theory of the independent individual as the basic unit of society is full of exceptions. When my own baby was awaiting birth, paddling away at my insides to strengthen her lungs and her bones, she was decidedly non-autonomous. She is swept out of moral consideration with the claim that she is not a person until she can survive without my involvement.

When the aged reach a certain point of weakness and inability, some doctors and ethicists are as ready to deny personhood at the end of life as they were at the beginning. The end of life is [sometimes] graciously excused as an exceptional time—there was a lot of autonomy in the middle, so the end can’t be held against the individual, or the theory.

All of this is nonsense. It would be fairer to say that dependence is our default state, and self-sufficiency the aberration. Our lives begin and (frequently) end in states of near total dependence, and much of the middle is marked by periods of need.

If we start with a false account of the human person, we cannot build a just society on that unstable foundation. If we imagine the ideal human person as autonomous, we shortchange everyone, but women bear a particularly heavy burden. We cannot convincingly pretend that no one depends on us and that we need no one.

The quote

One of my favorite articulations of who we actually are comes from O. Carter Snead’s What it Means to be Human.

Law and policy, animated by an anthropology of embodiment would view the mother as a vulnerable, dependent member of society, who is entitled to the protections and support of the network of uncalculated giving and graceful receiving that must exist for any human being to survive and flourish.

I asked him about this passage in our conversation. I often hear the capacities of the baby in the womb cited as the reason to protect his or her life, as we are trying to prove we can round them up to a full person. I rarely hear the limited capacity of both baby and mother cited as what makes them alike in dignity and both deserving of support.

The questions

Building the Benedict Option, my book on creating Christian community, revolves around two questions, which I think are also relevant to Other Feminisms readers.

What do you do alone that you could do together?

What do you do in private that you could do in public?

Both of these questions speak to how we build what Snead calls “the network of uncalculated giving and graceful receiving that must exist for any human being to survive and flourish.”

A culture that begins with an acknowledgment of our mutual dependence is one where need is visible. Not just in extremis, when you require help, but when you would like it but could technically manage alone.

In my book talks, I often ended by asking people to try asking someone for help in the next week, especially a kind of help they could do without, if needed, but would genuinely like to have.

Making a small ask opens the door to receiving a big one from a friend, a neighbor, a stranger who didn’t think that uncalculated giving and graceful receiving was a possibility here.

So, I’d like to close this anniversary posts with those two questions:

What do you do alone that you could do together?

What do you do in private that you could do in public?

And…

I love the ideas other folks have raised, especially bringing folks on errands and hosting game nights with babysitters. One I'll add is that it's fun to build/rebuild community around existing groups. A parent at my kiddos school has organized all the parents of the first grade class with playground dates and other activities - I'm plotting doing the same for our grade! I've also been hosting playdates for folks in my high school class who have kiddos (or who want to hang out with those of us who do!).

One idea I have for year 3 of your lovely substack is a series of interviews with folks who are living the kinds of values you discuss here. How have they managed to do it in practice? What do they wish they could have told themselves earlier on their journey? What was surprisingly hard or surprisingly easy?

Really love your substack and your way of thinking about our world! I pretty constantly live in community so dont do much alone. Id like to see more on the hows of sharing: how to share childcare, how to share meals, how to host bible studies, how to respond to big needs like refugees or sudden disability. I think many of us agree philosophically that women's lives could be better by sharing more, but what are the best practices? How do you avoid the pitfalls? And where do you find the people to do community with?