When Men and Women are Significantly Different

(...in the aggregate! And why that leaves a lot of room for individual expression)

This week, I’m talking about measurable differences between men and women… that still may not say much about any individual man or woman. On Thursday, I’ll share highlights from our conversation about disability and dependence.

And this Friday, I’ll be speaking at the Love and Fidelity Network conference at Princeton. My keynote is titled “Equality without Uniformity: We Can Do Better than Unisex” and you’re getting a preview of some of the material below.

Clearer Thinking is a site that aims to bring human behavior studies and insights to laypeople. They recently released a “Gender Continuum Test” that combines the appeal of internet-based personality tests with some useful background on what it means when we say men and women differ significantly in the aggregate on some particular trait.

(And, before you ask, when I took the quiz, my results lead their algorithm to assign a 72% chance of my being a woman).

What I liked best in their analysis came in a discussion of results that was a little buried in the quiz itself, so I contacted the site and asked them if they’d be up to pull it out as a standalone post, and they very graciously did so. You can read it here: “Gender and the Tail End of the Personality Distribution.”

You can (and should!) check out the whole, short post, but I want to highlight one of the key ideas. Men and women can differ significantly without that being a license for discrimination or constrictive stereotyping.

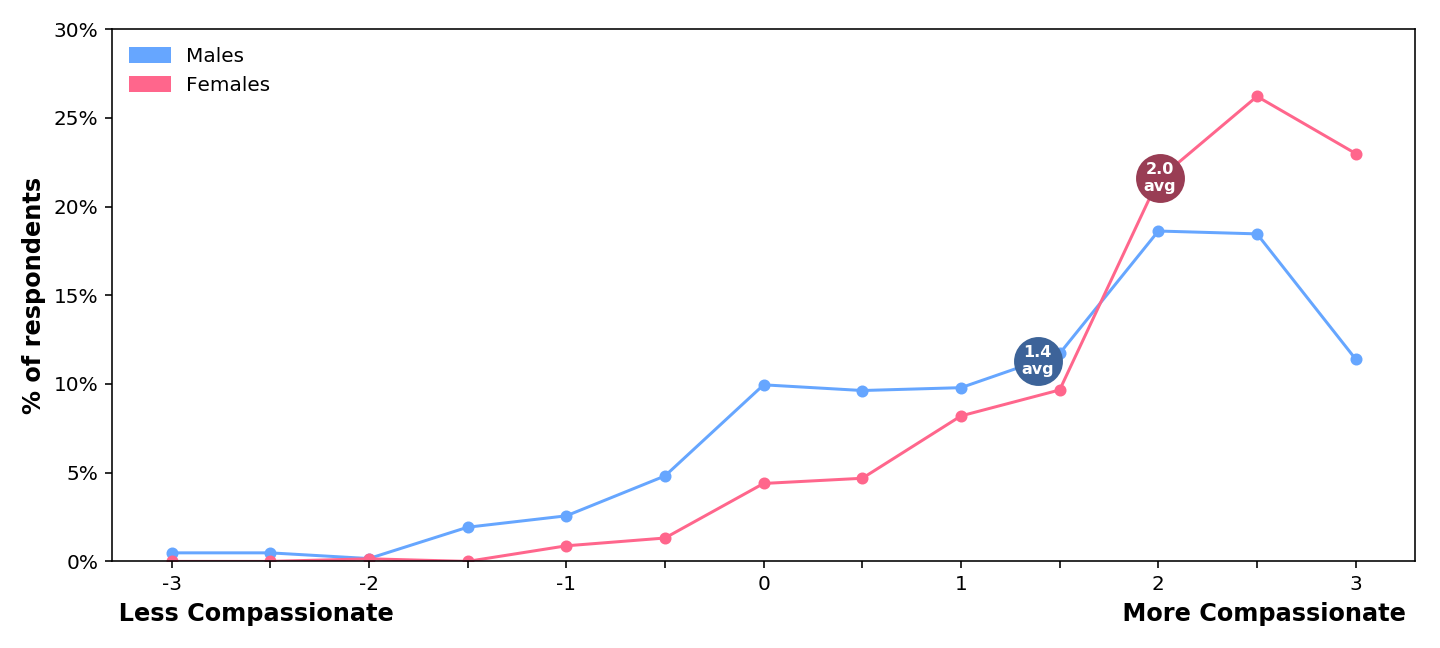

Clearer Thinking picks “Compassion” as the personality trait to highlight in this post. Here’s the distribution of male and female scores (self-rated) on this trait. (The scores are calculated by adding together a few different questions about compassion, not just asking people to rank themselves directly on compassion).

As you can see, the curves aren’t wildly different! You don’t see the two very distinct peaks of a bimodal distribution. That’s more what people imagine is true for men and women’s heights—less true than you’d expect, though. Grip strength is one of the most aggressively bimodal traits I’m aware of.

You might think, looking at the graph above, that compassion wouldn’t do much to meaningfully distinguish men and women. But, as the Clearer Thinking post explains, a trait doesn’t have to be limited to only men or only women to still cause you to meaningfully shift your expectations.

Imagine that you know the compassion scores of 100 people. The compassion scores alone would not allow you to guess with any reasonable level of accuracy who was male vs. female. This is because of the big overlap in the frequency of different compassion scores (especially in the range of 1.0 to 2.0) for men and women.

However, if you knew for a fact that a person had an extremely high compassion score (a score of 3), your guess that they are female would be about twice as likely to be true than if you guessed male. Likewise, if you knew that a person had a very low compassion score (e.g. -1.5 or lower) you would almost certainly be right if you guessed they are male!

I really appreciated their worked example, because it’s a helpful resource to link to on why a trait being strongly linked to gender isn’t the straightjacket it can sound like.

Knowing that a trait is more likely to be associated at the extremes with women or men is not the same thing as saying that a woman or man who doesn’t embody the trait is falling short in some way. It doesn’t mean that a man or woman who embodies a trait more strongly associated with the other gender is strange (or should seriously question his or her gender identity).

But it also doesn’t mean that men and women are so similar that we should talk as though sex isn’t relevant or is fading away to irrelevance. Analysis like Clearer Thinking’s doesn’t answer the question of how much of the linkage between personality and gender is biological versus sociological, but if the answer is “mainly biological” that isn’t a threat to women or men who don’t embody the extremes.

I like having a clear example of how saying “men and women have some notable differences” is not the same as saying “men can only X; women can only Y.” And it’s also a reminder of how it doesn’t take a huge difference for men and women to interact with the world differently.

In the New York Times, Jessica Nordell (assisted by Yaryna Serkez’s graphics) shows how a small sexist bias can produce big barriers to women for promotion. She uses a simulation to see how men and women move up a promotion ladder that isn’t closed to women, but where the company values any given woman three percent less than an identical man.

That small difference is enough to leave the higher echelons almost entirely male. When we’re interested in the extremes, it can take only a small difference to produce a painful gap.

Your observations unpack a recurring one of mine: that I have certain traits that seem to be more common in men than in women, or at least are more commonly associated with maleness (e.g. being highly logical and rational, being highly opinionated and quick to contradict, being competitive in games), though I have never had any inclination not to self-identify as female. This has long suggested to me what would appear to be confirmed by Clearer Thinking's analysis: that a) there are some tendencies that are broadly gender-based (as you say, in the aggregate), and b) these tendencies are not rigid and absolute. It also explains why I've never identified with types of feminism that indulge in male-bashing: I hear people denigrate "male" left-brained rationality, or "male" competitiveness as inferior to "female" compassion, and it hits a little close to home.

This is a minor point of detail, but it is frustratingly hard to conclude on the comparative distributions here because the data is so skewed to the upper end of a truncated range. I look at that graph and really want to have the compassion axis go to +6! With a range of -3 to +3, you don't want the median to be +2.5. (Acknowledging of course that creating the survey that gives this may be practically impossible.)

To make an analogy, it's like creating a graph of human height with a range of 5' to 6'. It would tell you a lot, but also leave out a lot.