When People Can't Be Replaced

Me on AI Therapists and The Origins of Efficiency

Delighted to share Patrick T Brown’s Dignity of Dependence review which calls the book, “a true manifesto” and gives me this incredible compliment: “Like C.S. Lewis’ depiction of Aslan, Sargeant is not a tame lion.” Your own reviews on Goodreads or Amazon very much appreciated!

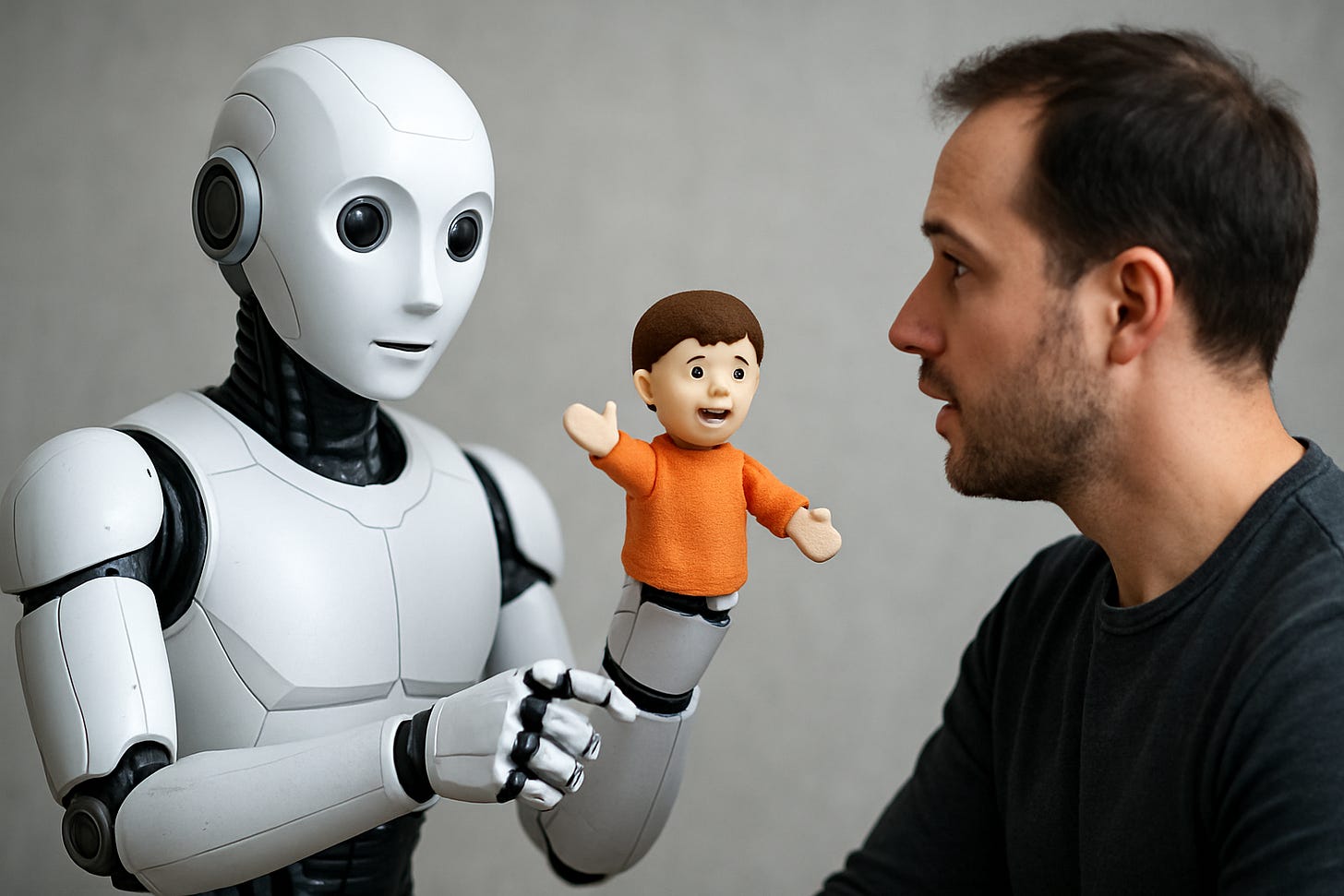

Meanwhile, in non-book news, I have two pieces this week on domains where we’re tempted to replace people with machines. First, for the Dispatch, I’ve got an essay on the (real!) good people are pursuing when they turn to AI therapists.

ELIZA is the most famous example of what might be called “placebo therapy.” Placebo therapy could involve talking to a bot or a friendly, untrained graduate student. In some trials, a nonprofessional interlocutor can do nearly as well as a trained therapist. In other analyses, some patients doing structured work on their own (like filling out worksheets on their habits of thought) do about as well as those working with a real therapist. Whether in a therapeutic context or elsewhere, many people benefit from a way to externalize and examine their thoughts. An interlocutor’s expectant silence prompts us to put into words ideas that were previously inchoate.

Programmers have their own way to get their thoughts outside their heads. Coders noticed that when they pulled aside a colleague to explain where they were stuck, they often spotted why they were stuck partway through their spiel, without their friend saying a word. Thus, some wondered, why not find a way to get the same effect without breaking into someone else’s workflow? “Rubber duck debugging” is the practice of debugging code with a small rubber duck as a partner. Explain your whole problem to the duck, and you’ll get to see if it’s the kind of problem you can solve yourself, once you get it outside your head. In the assumption that you may possess the solution unknowingly, rubber duck debugging is a cousin to Rogerian psychotherapy. For coders, it’s an efficient first pass at a problem. You can always escalate to a person if the duck’s silence fails you.

But debugging your program with a rubber duck is safer than debugging yourself with an LLM chatbot. After all, you can check if your code works by running it. You can’t as easily do a test run on your own sense of self-identity, to see if it fails to compile. When AI echoes back a user’s thoughts, it can reinforce harmful ideas. Verbalizing a paranoid or psychotic thought may give it more force than leaving it half-examined… It can be helpful to externalize your thoughts, but it’s not a good idea to believe everything you think.

And at Commonplace, I’m reviewing Brian Potter’s wonderful The Origins of Efficiency.

This is a book that my husband heard big chunks of, since there are wonderful The Way Things Work explanations of how penicillin, light bulbs, cigarettes, etc are made. Potter, who writes Construction Physics, makes his case for big breakthroughs in efficiency (even when upend old industries and jobs).

Making a product efficiently often requires making it into something new. The individually blown glass lightbulbs housing once-platinum wires were replaced by bulbs blown by a machine into a mold, displacing the glass blowers. The process was physically similar but standardized and automated, though it too was ultimately overtaken by something much stranger. The Corning Ribbon machine, invented in 1926, sent a current of molten glass flowing down a belt peppered with holes. Rather than gathering onto blowing pipes, it sagged through the holes into molds moving in sync with the ribbon of blazing molten glass, and was then blown out with precisely timed puffs. The first automatic bulb blowing machine, created in 1921, made blanks at the rate of 1,000 bulbs per hour. Five years later, the Corning Ribbon machine could produce 16,000 every hour.

When a bulb is made orders of magnitude cheaper and faster than the one that preceded it, it becomes a fundamentally different product. Efficiency overhauls aren’t just about increasing margins for owners, they’re about making it possible for certain products to exist at all. Although cost and personnel minimization is a part of industrial improvement, in Potter’s view, it’s not the fundamental driver of efficient processes. A truly efficient system isn’t one that has been cut to the bone, it’s one that operates continuously.

It’s a book that’s deeply romantic about processes… just what I love.

In The Dignity of Dependence, I’m curious about what could make people feel romantic about maintenance projects, and I find some intriguing answers from artists. As I write in “The Limits of Labor Language” chapter:

Wages and financial support matter, but when they can’t fully express the value of certain kinds of service and care work, what other ways are there to give this work its due weight? A number of female artists have attempted to limn this work with prestige by incorporating it into performance art. In one of my favorite pieces, Touch Sanitation Performance, Mierle Laderman Ukeles spent a year meeting and thanking each of New York City’s 8,500 sanitation workers. She offered a handshake to each worker she met, and she walked alongside them as they worked, covering full shifts. The best way to recognize the magnitude of this hidden work was with the duration of time it took to thank each individual. Spanning 1979 to 1980, Ukules’s work was a sort of pilgrimage…

Elevating maintenance as art allows us to see it as an expression both of mastery and of stewardship. To restore order takes an attentiveness to the material world; a sanitation worker doesn’t see generic garbage but has to be attentive to each bit of refuse as individual to determine what its future should be. Even when the sorting is done by machine, the factory line relies on the particular material properties of individual bits of detritus — metal recycling is hoovered up by magnets, light plastic bags are puffed by little jets of air over a gap into which heavier materials fall. Each type of refuse is carefully separated to see what new thing can be made.

Showing the value of care work similarly relies on shifting from viewing care work as an undifferentiated mass to individual moments, which agglomerate to a massive whole. In Sarah Maple’s 2022 Labour of Love she filled a room with 650 visual depictions of her nursing her baby — one for each nursing session over her baby’s first three months. Given room to sprawl, the ordinary work of mothering becomes monumental.

A love letter to maintenance, of many kinds, is Elizabeth Bishop's "Filling Station": https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/52193/filling-station (I have written about teaching this poem at West Point for Commonweal)

I WISH PURE HELL TO ANY MALE WHO USE FEMALE BODY AS 'THING'